On the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, the senior bishop of the German Evangelical Lutheran Church has preached at an historic Remembrance service in Ripon Cathedral attended by a record congregation of more than 1900 including young people, members of the armed forces, civic leaders and community representatives from across the city and region.

On the 100th anniversary of the Armistice, the senior bishop of the German Evangelical Lutheran Church has preached at an historic Remembrance service in Ripon Cathedral attended by a record congregation of more than 1900 including young people, members of the armed forces, civic leaders and community representatives from across the city and region.

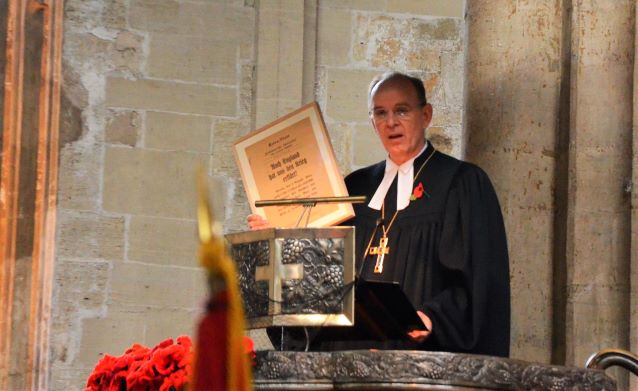

The Most Rev Ralf Meister, Landesbischof of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Hanover, (pictured left with Bishop of Leeds, Nick Baines), took part in the civic parade through the city to Ripon’s Spa Gardens for the two minutes silence at 11 o’clock, before using his sermon in a packed Ripon Cathedral to call on the church to unite in promoting peace and reconciliation.

"This war admonishes all of Europe to seek and strive for peace," said Bishop Ralf Meister. “I now see with dismay and even fear that many misdeeds of this history are being misappropriated by leaders such as Mr. Trump as examples to stir a new nationalism. Do we always draw the wrong lessons from history? Do we not see how easy it is to sleepwalk into war?”

"Peace needs passion. It is no dreamlike image, but a solid, most active option, for political action," said Bishop Meister.

You can view a German TV report on Bishop Ralf Meister's visit here. It was produced by NDR or Norddeutscher Rundfunk, a public radio and television broadcaster, based in Hamburg.

The Cathedral was full with standing room. Civic leaders included Mr Richard Compton, Deputy Lieutenant of North Yorkshire, representing Her Majesty The Queen, and the Mayor of Ripon, Cllr Pauline McHardy

The Cathedral was full with standing room. Civic leaders included Mr Richard Compton, Deputy Lieutenant of North Yorkshire, representing Her Majesty The Queen, and the Mayor of Ripon, Cllr Pauline McHardy

In his sermon, Bishop Meister also gave an insight into the German perspective on the First World War. “The people of Germany saw the (First World] War as a just cause. For them it was a defensive war.”

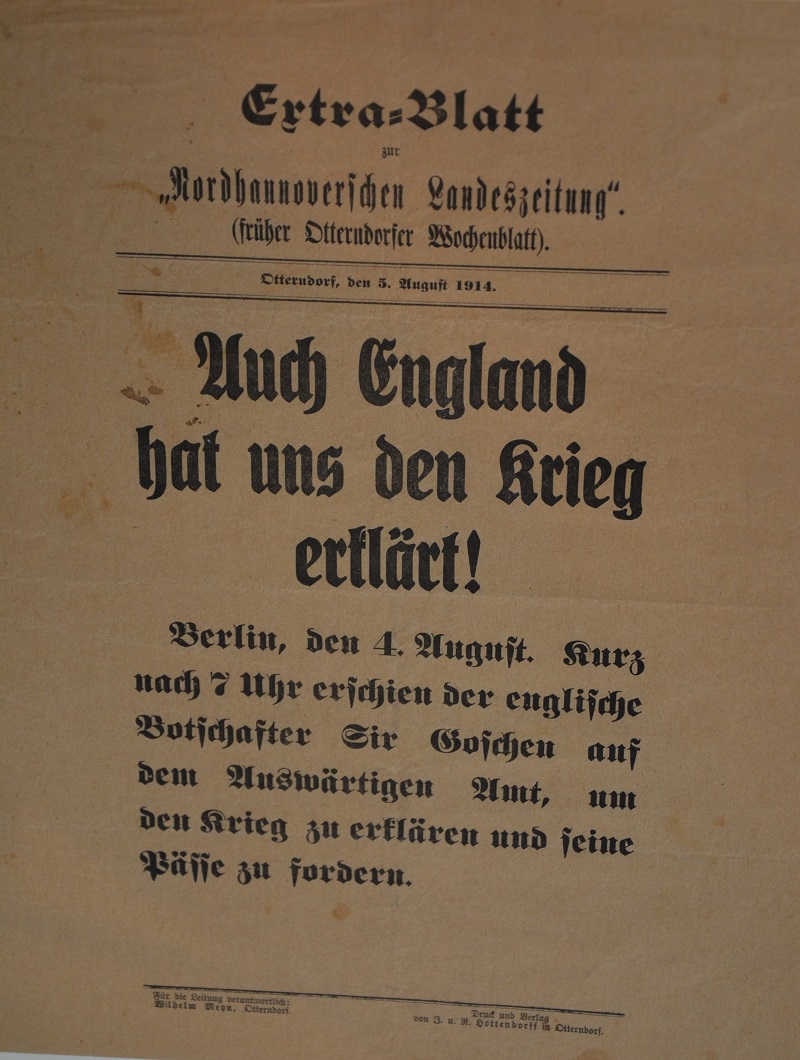

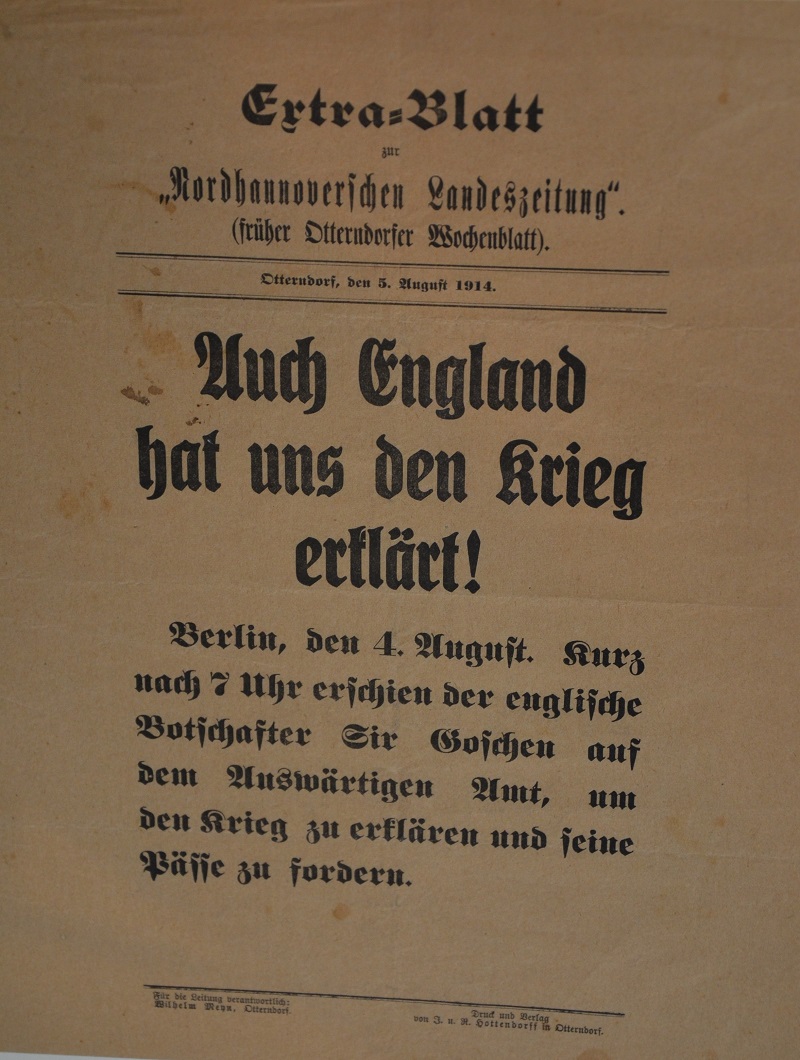

He held up a headline (pictured right) in the North Hannoverian rural paper of August 5, 1914 which reads ‘Now England too has declared war on us!’. “This special edition of the North Hanoverian paper has stood mounted on the piano in my living room these last four years. It is there to keep me reminded that this war was not just an event locked in history books … it lives on in the memories of our families and our cultures, in England, in France, in Russia and in many other countries.”

Read Bishop Ralf Meister’s sermon in full below.

The delegation from Hannover also included the internationally-renowned Hannover Girl’s Choir - the ‘Madchenchor Hanover’ – which had also sung on November 10th at Halifax Minster. They sang two anthems in the Ripon Cathedral service ‘Peace Upon You Jerusalem’ by Francis Poulenc, and ‘Sanctus’ by Caplet.

The delegation from Hannover also included the internationally-renowned Hannover Girl’s Choir - the ‘Madchenchor Hanover’ – which had also sung on November 10th at Halifax Minster. They sang two anthems in the Ripon Cathedral service ‘Peace Upon You Jerusalem’ by Francis Poulenc, and ‘Sanctus’ by Caplet.

Ripon schoolchildren joined the military and civic parade through Ripon, each bearing a poppy with the names of one of the Fallen. These were laid at the war memorial at the cathedral’s high altar during the service. There was also music from the Dishforth Military Wives Choir, while Ripon Cathedral Choir sang the anthem ‘Armistice’ by Philip Wilby.

Bishop of Leeds, the Rt Revd Nick Baines, spoke of the friendship between the two dioceses of Hannover and Leeds. "Our commitment to the Christian Gospel is that we must be 'makers' of peace and not just 'lovers' of peace." And he said that it was a great honour to welcome Bishop Meister and the Hannover Girls’ Choir. “In their visit is a symbol of the unity of God’s people.”

Bishop of Leeds, the Rt Revd Nick Baines, spoke of the friendship between the two dioceses of Hannover and Leeds. "Our commitment to the Christian Gospel is that we must be 'makers' of peace and not just 'lovers' of peace." And he said that it was a great honour to welcome Bishop Meister and the Hannover Girls’ Choir. “In their visit is a symbol of the unity of God’s people.”

Bishop Ralf Meister - Sermon given 11.11.2018, Ripon Cathedral.

Grace to you and the peace from God our Father and Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

When my grandmother died almost thirty years ago now, her entire family gathered together. In the weeks after her burial we needed to empty out the large farm house in which she had spent her entire life. In the course of doing this, we found an old magazine binder of 1877, a ‘Chronicle of Current Events’, and in this volume a copy of a daily newspaper. It was a special edition of the North Hanoverian rural paper of  August 5, 1914. To preserve it for posterity, someone had inserted it into a thick magazine binder. Printed in bold letters the headline read: Now England too has declared war on us! And below with the dateline Berlin, August 4: “Shortly after 7 o’clock the English ambassador Sir Goschen appeared at the Foreign Office to declare war on us and to demand his passports.”

August 5, 1914. To preserve it for posterity, someone had inserted it into a thick magazine binder. Printed in bold letters the headline read: Now England too has declared war on us! And below with the dateline Berlin, August 4: “Shortly after 7 o’clock the English ambassador Sir Goschen appeared at the Foreign Office to declare war on us and to demand his passports.”

These printed lines were only possible because, just days before, on the First of August the German Reich had declared war on Imperial Russia, and on the Third of August it had declared war on France. It had taken all of six weeks in the summer of 1914 for the world to tumble into a global war.

Weeks of crises commenced with the murderous assassination of Sarajevo. There followed the steeply horrendous decline of relations among Europe’s most powerful states. Forget diplomacy, reach for arms. Above all in Germany great jubilation and war fever were rampant. Flags flew, church services were held, divine help for this armed conflict was asked for and soldiers rolled away, with merry laughter and joyous waving as the trains headed for the front lines, in railway carriages which bore scrawled chalk messages such as “Off to the prize target shootout in Paris!”

After the wars of the last hundred years, we now look at these displays of jubilation with great disbelief. How could these killings possibly fascinate? In honour of precisely what did these people head for their deaths? And what sense of mission could these men possibly have felt as they were exposed to cruel enemy gunfire in the trenches for months?

Wilfred Owen, the renowned English chronicler of the days of the Great War wrote:

“My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory, the old lie:

Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.”

It is a sweet and honourable thing to die for one’s country. (Roman poet, Horace.)

One hundred years ago on November 4, 1918, just days before the war’s end, Wilfred Owen was killed in France at the age of twenty-five. We marked his passing in remembrance a week ago in Hanover, at a performance of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, by orchestra and choristers from Liverpool and also the Hanover Girls’ Choir.

This special edition of the North Hanoverian paper has stood mounted on the piano in my living room these last four years. There to keep me constantly reminded that this war was not just an event locked in history books. These wars are still with us in our family histories, three and four generations on. My grandfather, whom I particularly loved as a child, volunteered with eagerness and passionate enthusiasm at the age of not even seventeen to go to war. He was badly hurt in a poison gas attack.

This war is not just a dreadful chapter of European history, but it lives on in the memories of our families and our cultures, in England and in Germany, in France and in Russia and in many other countries. But today, this war admonishes all of Europe to seek and strive for peace. With this war our continent was deeply torn.

Memorial tables are to be found along the inside walls of nearly all evangelical churches in Germany, as here in Ripon Cathedral, recalling the men who had, as it was phrased back then, “gone to their death” in the First World War. ‘We will, we will, we will remember them’. There they are, the names of those of the village who had died for the ‘honour of their native land.’ Strikingly, almost everywhere only the names of the mortally wounded soldiers are recorded on these memorial plaques in our churches. To this day and almost without exception, hardly ever do we find a visible record of the names of peace activists or of female and male emergency helpers. When will we, in our churches, memorialize the names of the witnesses to peace?

The people of Germany saw the war as a just cause. For them, it was a defensive war. Although Germany had not been attacked, many people were under the impression that they needed to defend themselves. People in all European countries at this time were persuaded to go to war in order to defend themselves. They felt themselves deeply enjoined in the destiny of their nations. Let’s be honest. This attitude strikes us as familiar. Yes, this attitude is now and throughout the world gaining currency and appeal. We are all engaged in a ‘defensive posture’, wanting to defend our cultures and our national sovereignty with much passion and deep feelings. And we blend in elements of resentment and rejection.

But our language coarsens and turns hostile as we defend ourselves. And faster than we intended, this defensiveness turns into attack: an attack in the struggle for our innate ‘own core.’ I can see how delimitation comes about. We turn on people ‘outside’, as well as those ‘within,’ that is to say, against all who do not share our views. It almost seems as if the words of Wilfred Owen are as fitting now as they were a hundred years ago:

“Now begin famines of thought and feeling. Love’s wine’s thin.” (W. Owen, 1914)

I thought for a long time that the history of catastrophes of the twentieth century was THE primeval story of educating the human race for that which is ‘Good.’ I thought that it was the story calling us to love, the story that would appease our thoughts and feelings with a passion for peace. I now see with dismay and even fear that many misdeeds of this history are being misappropriated as examples, by leaders such as Mr. Trump, to stir a new nationalism. Do we always draw the wrong lessons from history? Do we not see how easy it is to sleepwalk into war?

For the upcoming year 2019, the German Protestant and Roman Catholic churches have chosen a quote from the Bible as watchword or motto for the year. In the 34th Psalm it reads: “Seek peace, and pursue it.” I have welcomed with joy the choice of this quotation. It is a call on the churches, but also a word of caution for all of Europe. Seek and search for peace! Whoever wrote these words almost three thousand years ago knew that peace is not something that just happens when war is over. Peace calls for energy, courage, conviction. Peace is not an empty theological vision. Peace needs passion. It is no dreamlike image, but a solid, most active option for political action.

Both languages, the English and the German contain many verbs dealing with fighting, but no single verb that deals with peace. To make peace, to shape peace might well be termed: to get to know each other better. To seek to understand. Peace means to accept that we are distinct, yet encounter one another in love. Peace means forgiveness, without a compensatory return service, to practice hospitality and to learn from each other. We are in need of verbs for peace! In German the definition is ‘words of action’.

How very much I wish that we, as Christians (and members of other faiths and none), and not just between our dioceses of Leeds and Hanover, were ambassadors of peace between our countries. This, at a time when building walls is ever more popular. Let it be a call to surmount borderlines between nations and races in Christ Jesus.

Never again, never again, do we want to see in Europe, or throughout the world, special issues of newspapers with these banner headlines. Let us pursue peace. Together!

God unites us in the spirit of Love, transcending all borders.

In Time. And Eternally.

Amen