Doctors, nurses and medical staff have joined mayors and civic dignitaries at a special diocesan service at Ripon Cathedral to mark the 70th anniversary of the NHS.

Doctors, nurses and medical staff have joined mayors and civic dignitaries at a special diocesan service at Ripon Cathedral to mark the 70th anniversary of the NHS.

Dean John Dobson led yesterday's Choral Evensong, which featured poignant recollections, readings and the voice of Aneurin Bevan reflecting on the NHS in 1959.

Bishop Nick was to have officiated, but was unable to attend due to ill health.

"Sadly, he's in bed with a temperature - I told him he should have called a doctor," quipped the Dean.

90-year-old Cathedral congregation member Geoff Johnson read the stark testimony of a 91-year-old Bradford man, who recalled how grinding poverty and lack of medical care before the NHS led to his sister's early death from TB in a public workhouse.

Ripon GP Dr Charles McEvoy then spoke of his role in providing NHS care via his private practice and of the increasing pressures due to an aging population and greater demand for preventative medical treatment.

He said it was a privilege to serve the local community as a GP, especially as the fourth generation of his family to do so.

Revd Yvonne Callaghan, vicar of Brompton on Swale, spoke movingly of how NHS renal treatments and kidney transplants had saved her life and let her fulfill many goals, including becoming the mother of two sons, one of whom has also needed a kidney transplant.

Chaplain of Harrogate District Hospital, Revd Sue Pearce spoke of the bravery shown by patients and staff, often using "masks of perfomance" to conceal emotion during tough times and also how they often relish talking with her as an informed, yet slightly removed third party.

"One thing though, is never ask anyone if they are having a quiet day!" Revd Sue said.

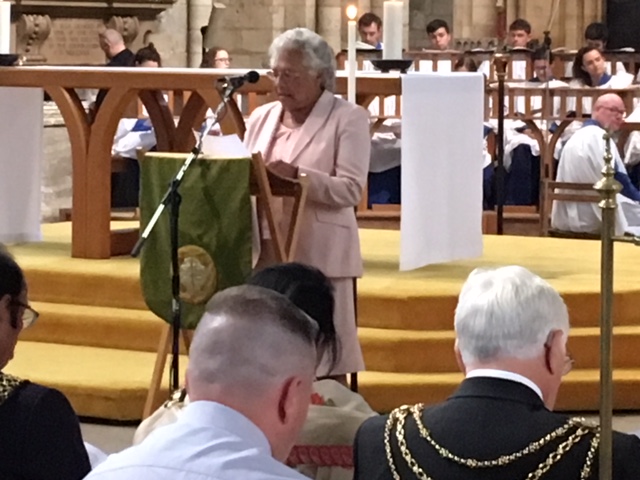

Nurse Monica Sharpe (pictured above), who is the longest serving member of staff at Harrogate District Hospital and has just celebrated her own 70th birthday, gave the New Testament reading.

Born in Trinidad, the day after the National Health Service was launched, she moved to Yorkshire at the age of 21.

Next August, Monica will have served as a nurse in the Harrogate NHS Trust for 50 years and said: “I’m very proud of my time in the NHS, I’m hoping I live to make it to 50 years because I’m still working, I’m still nursing so I’m not planning on leaving and they don’t want me to go!”

A visiting choir from St Luke's, Chelsea sang beautifully throughout the service - particularly the anthem with poignant words from Sirach and Isaiah: "Strengthen ye the weak hands, and confirm the feeble knees.

"Say to them that are of a fearful heart, be strong, fear not: behold, your God will come; he will come and save you."

The front rows of the cathedral were packed with civic representatives from across the Anglican Diocese of Leeds, including the Mayor of Bradford, Cllr Zafar Ali and his wife the Mayoress, Zeabunnessa Zafar (pictured).

The front rows of the cathedral were packed with civic representatives from across the Anglican Diocese of Leeds, including the Mayor of Bradford, Cllr Zafar Ali and his wife the Mayoress, Zeabunnessa Zafar (pictured).

Dean John read Bishop Nick's address, which is printed below in full, and the blessing was given by Bishop of Ripon, Dr Helen-Ann Hartley.

NHS 70 Service, Ripon Cathedral

Sunday 29 July 2018

"Earlier this month I did the Thought for the Day on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. I was specifically asked to reflect on the 70th anniversary of the NHS - which I was happy to do. However, within 30 seconds of finishing the broadcast, the first email popped into my Inbox - criticising me for praising the NHS when there are, as they say, other variants available. Usually it takes at least a minute before the criticism or abuse starts to come in, so this was a bit of a record. But, why should someone take such offence at a simple recognition of the National Health Service on its 70th birthday?

Perhaps the root of the accusation was that I used a difficult word. Former Prime Minister Gordon Brown said this: “Of all the words used by Bevan to describe the benefits of the NHS, the one he returned to most was a word we rarely use today - serenity. After years in which great-grandparents, grandparents and parents had no peace of mind when their loved ones were sick, because they simply could not afford the treatment, serenity was what the NHS provided. It still does.”

Isn’t that just perfect? ‘Serenity’. The peace of mind that separated health care from the anxieties of affordability - and in an age when children and adults could easily die of diseases that, even in their day, could be cured.

We take this too easily for granted. We assume in the twenty first century that health care is a right. Sometimes we push this too far, the language of “fighting” cancer or other diseases implying that such things should not happen to us - that we have some inalienable and unquestionable right to a long life and full health - when, in fact, we are mortal beings in a finite world, whose fundamental reality is that we shall all die. Yes, we can protest too much. But, what the NHS affirms is the common mutual obligation we have in a good society to care for one another ... and to recognise that the life and health of any individual has an impact on the life and health of everyone else. Hence, we look to the interests of all in our society.

The other thing we might take too easily for granted is where this (what I might call) ‘humanism’ comes from. Remember that for centuries and millennia life was brutal and cheap; people were expendable. Attempts to read back into the great Classical empires some benign generous humanism are take clearly to task by the historian Tom Holland who came to question his assumptions and recognise that the sort of humanism we are speaking about here came directly from a Christian theological anthropology. Let me explain.

Human beings are made in the image of God. This, ultimately, is why each one matters. Not their economic utility; not their factual interrelatedness - important though that is; not their achievement or wealth or productivity: simply, that they have infinite value as made in the image of God. Yet, in turn, this createdness is what lies at the heart of human mutuality: we belong together, not by choice or preference, but because of our common origin and value. Put at its simplest, the NHS rests on these pillars: a free and just society takes all its people - and their wellbeing - seriously, and is willing to invest financially in the common health. Hence, regardless of income or value attributed by others, everyone has access to health care at some basic level, at least.

Writer Mark Haddon put it like this: “The true worth of the NHS is that those of us who are lucky enough to pay tax can go to sleep at night, knowing that we have helped make that radical kindness possible.” ‘Radical kindness’.

Now, this is not to say that the economics are simple. Health has to be paid for. The NHS demonstrates a model that assumes that some pay more - according to ability to pay through taxation - and others less. Yet, look at some basic facts: since 1948 and the birth of the NHS life expectancy has risen by an average 13 years (which now provokes further challenges); infant mortality has dropped from 34 in every 1000 births to 3.8; half of people with cancer now survive for a decade or more; and so on. Yet, there can still be massive discrepancies in life expectancy between the affluent and the deprived in adjacent areas of the country.

So, this celebration of 70 years of the NHS is no invitation to some blind fantasy about future health care or the choices and costs associated with it. Today is no bland political hooray for a service that too often has served as a football for newspapers and politicians. We can be realistic about the challenges whilst celebrating the achievements thus far.

It is here that I want to get to the heart of what makes the NHS work: it’s staff. I know that there are massive challenges in recruitment and departures, and that these do not look like being addressed adequately in the short term. And here I speak not only of doctors and nurses, but also of managers, administrators, porters, cleaners, call handlers, paramedics, and everyone who makes the service work - often at the expense of a deep commitment that sometimes feels unrecognised or inadequately rewarded. Just read Adam Kay’s hilarious, but sobering, memoir ‘This is Going to Hurt’. Or the dilemma articulated by Dr Phil Hammond: “I often wonder if I’ve done more good for people’s health as a comedian than as a doctor. Laughter is the best medicine, unless you have syphilis, in which case it’s penicillin.”

And this brings us back to the point. Human beings cannot be split conveniently into separate compartments labelled ‘body’, ‘mind’ and ‘spirit’. Christian theology is clear: the human being is a psychosomatic unity that must be treated as a whole. What happens in our mind impacts our body and sense of spiritual value. If my body is hurt, I don’t just carry on as if nothing has happened to my life and way of thinking.

This is why, in our New Testament Reading from Luke’s Gospel, we see that this woman’s healing was not merely a private matter for her. There is a social impact from her healing: it comes at cost to Jesus himself, then is publicly admitted and owned. Health is never simply a private matter - at least, as long as we recognise the common nature of human being and obligation. When the woman goes in peace - or might ‘serenity’ fit as the right word here? - this clearly has something to do with her social relationships, her new social reality as a well woman, and the obligations her new status imposes on her and those around her. Health is not neutral. And if people - the recipients of health care - are to be valued as body/mind/spirit whole entities, then so must the rest of society allow the same for those who make that health service work for the common good.

Did you notice that that Gospel Reading was framed by the choir singing the Magnificat and the Nunc Dimittis? The former comprises a song sung in anticipation of a birth, the latter presages a death. The Magnificat echoes a song by another woman centuries before in the Old Testament narrative. Here Mary, hearing she is to give birth to a baby who will grow into a man who will turn the world upside down (not something most young women would feel entirely positive about - it sounds like there will be trouble ahead), opens herself to a future that cannot be controlled. This is realism - the recognition that responsibilities are being forced on her by circumstances and people beyond her capacity to order. That is real life. Read in the Gospels how this looks as her son, Jesus of Nazareth, grows into the man who gets crucified by the Roman powers.

Then, in the Nunc Dimittis, an elderly man realised that his time is up, his death drawing near. Yet, rather than desperately try every method to stay alive at all costs, he is at peace with his mortality. He also doesn’t know the end of the story - he knows he won’t be around to see what happens to the baby he has just blessed. But, he has seen enough. He is at peace with his living and his dying.

The thing that joins these two people and these two songs is that birth, life, disease and dying can be approached without fear. These are the natural elements of what it means and involves to be human and mortal and contingent in a messy and uncontrollable world. This, I think, is what Bevan captured when he used the word ‘serenity’ to describe the achievement of the NHS in re-shaping the life of generations to come.

Despite all the challenges and debates about the future of the NHS, this is what we celebrate today. Thank you to all who work in this region to offer serenity to those for whom living and dying might prove more difficult than for others. Thank you to those who administer and manage our services; those who work at the IT services and communications; those who keep our facilities clean and habitable; those who constantly work beyond the terms for which they are rewarded financially; and all who work hard to ensure that what is too easily taken for granted by the comfortable and complacent usually works ... bringing serenity to people for whom the lack of it would prove quickly destructive.

I conclude with a story to cheer you up in relation to the realism I have been encouraging this afternoon. A man isn’t feeling very well, so his wife takes him to the hospital where he undergoes a series of tests. While he is getting dressed again, the doctor says to the wife: “Now, look, this is serious. He has to have a minimum of ten hours sleep every night, three meals a day every day, beer on tap while watching sport of his choice on the telly, and he is to have sex seven times a week ... or he’s going to die.” In the car on the way home the husband says to the wife: “What did the doctor say, dear?” She said: “You’re going to die.”

But, as the singers of the Magnificat and the Nunc Dimittis grasped, ultimately death will not have the last word."

The Rt Revd Nick Baines, Bishop of Leeds.